Featured Sounds

Yellow-headed Parrot (Amazona oratrix)

The Yellow-headed Parrot is considered endangered in its native Mexico where fewer than 7000 birds may remain (NatureServe). But in a twist of fate, small populations of the bird exist in the Los Angeles area, including the San Gabriel Valley and parts of Orange County. These birds are thought to be descendants of escaped pets and are found in flocks around various residential and suburban locations.

Audio recordings of the Yellow-headed Parrot are rare, so the Western Soundscape Archive recently visited Pasadena where the species is often spotted. After consulting the The California Parrot Project, which monitors wild parrots in the region, and with the help of local residents we located a known roost site and set up our microphones to capture a few calls.

Dozens of parrots arrived like clockwork around sunset and again the next morning at sunrise. It turns out that the flock also included many red-crowned parrots, which are also introduced to the area— and also endangered. The calls of both species were unmistakable. Residents of the neighborhood have become used to this daily cacophony as birds descend upon palm trees, telephone poles and whatever serves as a suitable resting place.

Hear sounds from the recording trip, including the Yellow-headed Parrot the Red-Crowned Parrot, a flock of both species and watch a short, impromptu cell phone video.

Sources: The California Parrot Project;

NatureServe

American Bison (Bos bison)

An estimated 30 to 60 million bison once roamed across North America. By the end of the 19th century, hunters had wiped out all but about 600 of the species. Bison were killed for profit and sport by American settlers, and by the U.S. Army to control Native American tribes that depended on the animals. Due to conservation and breeding efforts, about 30,000 bison are now found in public or private parks or preserves, while another 400,000 are raised as livestock.

One of the nation's oldest free roaming bison herds is found on Antelope Island in Utah's Great Salt Lake. The herd of 600 grew from just a dozen animals brought to the island in February, 1893. Listen to recordings made by the Western Soundscape Archive during the park's annual bison roundup.

Bison facts: The bison is the largest land mammal in North America. It weighs up to 2000 pounds and can stand more than six feet tall at the shoulder. Bison tend to be most vocal and aggressive during their breeding season from mid-July through August. Most of the destruction of bison herds in North America occurred during a 55-year period— from 1830 to 1885.

Sources: NatureServe; National Park Service: Frequently Asked Questions about Bison; Wind Cave National Park

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northeastern Alaska. The Refuge was created on December 6, 1960, and has come to be one of the great symbols of American wilderness.

The Refuge is vital ground for animals such as the Caribou, Arctic Fox and Brown Bear, and millions of migratory birds gather here each spring and summer to breed and prepare for their long journeys south. During that time the birds and other animals call throughout the day and night, taking advantage of the constant daylight that occurs in northern latitudes during this season. The result is one of the world's premier natural soundscapes.

In early June of 2006, three teams of recording engineers traveled to the Refuge to systematically capture the sounds of this remote and wild region. From the period of June 2-11, audio recordings were made at three locations representing different biomes: Timber Lake (boreal/taiga/tundra), Sunset Pass (foothills/tundra) and Beaufort Lagoon (coastal plain located within Refuge Area 1002, a site of proposed oil and gas exploration). These recordings can be heard here as part of the Arctic Soundscape Project.

Arctic recording team member Dr. Bernie Krause writes: "From the audio data we will be able to extract and analyze (l) organism presence and density, (2) acoustic characteristics of the habitats and landscapes (3) provide a baseline collection against which to measure future impact of human noise, climate, and habitat changes within those sites, and (4) provide audio data for a wide range of applications for science, education, the arts, and conservation advocacy."

Search recordings from the collection or listen to selected highlights. Special thanks to Dr. Bernie Krause, Martyn Stewart and Dr. Kevin Colver for the use of their Arctic recordings.

Sources:

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge;

The Arctic Soundscape Project

Moose

The Moose (Alces alces) is the largest member of the deer family and ranges from the Rocky Mountains to the northern United States and Canada. It can reach a height of 7 ½ feet at the shoulder and weighs up to 1,300 pounds.

Typical habitat for the species includes second-growth forests near open areas of wetlands and lakes, where it forages for aquatic plants. It also feeds on the new growth of trees and shrubs in the summer while subsisting on conifer and hardwood twigs in the winter.

Breeding season extends from September to October when males go into rut and compete for mates. Vocalizations during this time can include loud bellows and barks, while other sounds throughout the year range from moos and grunts to moans. Listen here to a female calling to her two sub-adult calves as they swim to a small island in the middle of an alpine lake in Utah. As the three emerge from the lake, one gives a powerful grunt close to a microphone on the shore.

Sources:

Peterson Field Guides: Mammals of North America;

NatureServe

Rolling Thunder

A lightning bolt flashes for just a brief moment, but the roll of thunder can last much longer— sometimes for a minute or more. This is because of the speed of sound and the relative length of a lightning bolt.

As a bolt of lightning moves through the sky, it heats the air around it to more than 43,000 degrees, creating explosions as it moves. Imagine a string of firecrackers exploding one after the other as the lightning moves up the string. The further away the explosions are along the lightning bolt, the longer the sound takes to reach us, and thus we hear the explosions one after the other as a progressive rolling sound.

Given that the speed of sound is approximately 1,100 feet per second, it's easy to remember that every second of sound corresponds to about 1,000 feet of distance. Thirty seconds of rolling thunder, for example, means that the actual lightning bolt is roughly 30,000 feet in length. The longest lightning bolt ever measured was 118 miles in length, recorded in the Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas area.

Measuring the length of a lightning bolt is not the same as calculating how close a bolt has struck. For that well-known trick, you count the seconds between the flash and the first crack of thunder. Listen to recordings.

Sources:

NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory

American Pika (Ochotona princeps)

The American Pika is a small rabbit-like animal that lives in mountainous areas of the western United States and Canada. The species typically inhabits rocky talus slopes, and is often found near or above tree line.

It is adapted for life in cooler temperatures, which some conservationists believe makes it especially sensitive to global warming. "A key characteristic of the American pika is its temperature sensitivity; death can occur after brief exposures to ambient temperatures greater than 77.9° F," writes the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that average summer temperatures in the West could rise by about 5 degrees Fahrenheit by mid century, potentially changing available vegetation for forage and diminishing suitably cool habitats. However, the United States recently declined to list the American Pika under the Endangered Species Act, arguing that the species will be able to survive by moving to higher elevations.

The conservation database NatureServe lists the status of the American Pika as secure, but there is evidence of some regional population declines. A study by Beever et al. (2003) showed a 28% decline in historically reported populations in the Great Basin.

The American Pika makes a variety of vocalizations, including nasal whistles and short barks. You can listen to some of these sounds on our website.

Sources:

NatureServe; US Fish and Wildlife Service; NOAA

Ironwood Forest National Monument

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the creation of the Ironwood Forest National Monument in southern Arizona. Established on June 9, 2000 by president Bill Clinton, the monument protects 129,000 acres of classic Sonoran Desert habitat. More than 400 different plant species are found here and dense stands of ironwood trees and saguaro cactus define the region. At least 57 different bird and 64 mammal species help create one of the desert's most iconic soundcapes.

The drought resistant ironwood tree for which the monument is named is the ultimate desert survivor and can live for more than 800 years. The tree provides food and cover for wildlife and enriches the surrounding soil with nitrogen, in turn benefiting other plants. Its wood— so dense that it doesn't float— can remain on the desert floor for 1600 years, continuing to offer cover and places for birds to sing.

The Western Soundscape Archive visited Ironwood Forest National Monument in April 2010 and made baseline recordings to document the sounds of the area. You can hear some of these recordings on our website, or view a slideshow of photos taken at the recording location. Listen for white-winged and mourning doves, curve-billed thrashers, cactus wrens, Gila woodpeckers and many other common desert species.

Sources:

Ironwood Forest National Monument

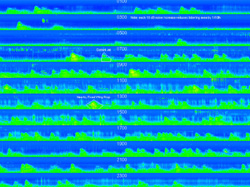

More than 80% of the land in the continental US can be found within a mile of a road.1 Automobile traffic has tripled since 1970 and airplane flights are nearly ubiquitous, tripling since 1980. 2 Fast growing populations mean more people on the move, and the result is a chronic rumble of engine noise that spreads across the landscape.

We pay a price for this. Areas that may still look the same often don't sound the same, and there are significant ecological effects. Hearing is a vital sense that alerts animals to predators or to the presence of prey, and sound is one of the primary ways that animals communicate, particularly for reproduction. Human-caused noise can mask sounds and interfere with these fundamental activities, worsening other serious problems facing wildlife. Studies have also shown links between noise and adverse health effects in humans, such as high blood pressure and hearing loss.

Visit the Western Soundscape Archive's spectrogram collection to find out more about noise and how the National Park Service is monitoring noise effects in natural areas.

Photo courtesy of USGS

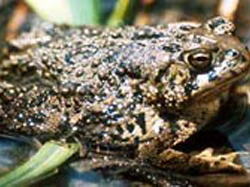

The Southern Mountain Yellow-legged Frog is close to extinction and is found in the southern Sierra Nevada mountain range and parts of southern California. Fewer than 2000 adults of the species are thought to remain (NatureServe) as populations continue to decline due to habitat loss, exotic species (primarily introduced trout), and disease such as chytrid fungus which is devastating amphibian populations worldwide. It now occurs in less than 5% of its historic range.

Going by the scientific name Rana muscosa (muscosa being Latin for "mossy" in reference to the frog's blotchy coloration), the species calls underwater and is distinct from most other calling amphibians because it lacks a vocal sac and makes sounds by grinding its teeth. It typically breeds from March to June in lower elevations and from May to August in higher elevations depending on area snow pack.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service lists certain populations of this species as "Endangered" while some populations remain under "Candidate" status. Listen to rare recordings of this species.

Sources: NatureServe Explorer; US Fish and Wildlife Service; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Amphibiaweb

Northern Elephant Seal Mirounga angustirostris

The Northern Elephant Seal is found in the Pacific Ocean as far west as Japan and Hawaii and breeds along the coasts of California and northern Mexico. The seals get their name because of their mammoth size and the male's large snout, which inflates and aids in vocalization. Females are 6 1/2 - 10 feet in length, while males can grow to 16 feet and weigh up to 6000 pounds.

The species spends about nine months of the year at sea, but comes ashore in the winter to breed. Large colonies can be found on coastal beaches and offshore islands as males compete for mates in dramatic fights and displays. A single dominant male can have a harem of 25-50 females.

Once hunted to near extinction in the late 1800s, the Northern Elephant Seal population is now stable due to conservation measures and has risen to more than 100,000 animals. Hear selected recordings.

Sources: Peterson Field Guide to Mammals; Ano Nuevo State Park; Friends of the Elephant Seal

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature one in five mammals, one in eight birds, and nearly one in three amphibians worldwide are now threatened with extinction. Scientists say that human alteration of the environment is the chief cause, and that we face one the largest mass extinctions in the planet’s history.

The western United States is no exception to this trend. Many of the animals heard in the Western Soundscape Archive are threatened or vulnerable due to factors like habitat loss, climate change and pollution. Listen to just a few of these disappearing voices here.

The Western Soundscape Archive works to raise awareness of regional biodiversity by preserving the sounds of animals and their environments, and recognizes the crucial need for conservation worldwide. You can find up-to-date conservation information for every animal in the archive’s collection courtesy of NatureServe. Scroll to the bottom of each species record and click on “Conservation Status.”

Sources: IUCN Red List; Natureserve; Amhibiaweb

Photo courtesy of U.S Forest Service

Bark beetles are a growing threat to pine forests across the American West and Canada. “By about 2012, beetles will have killed nearly all of the mature lodgepole trees in northern Colorado and southern Wyoming,” reports the US Forest Service, and tens of millions of acres of pine and spruce from New Mexico to British Columbia have already succumbed in recent years.

The tiny beetles, each about the size of a grain of rice, have always been part of the forest ecology, but some scientists believe their increase may be a consequence of climate change. Beetle populations are aided by milder winters, and increased drought can make trees more vulnerable.

Listen to the sounds of these beetles, as recorded by composer and audio engineer David Dunn.

Sources: US Forest Service; Associated Press; Acoustic Ecology Institute

|

|

|

Bottom row photos courtesy of US Forest Service

Elk Cervus canadensis

Elk once ranged throughout North America, but are now found mostly in mountainous regions of the western United States. Their classic bugling call can typically be heard from late August and into October when males call to females during the rut. The Western Soundscape Archive recorded these calls in northern Utah at dusk in late September of this year.

Musicians might notice that the sweeping elk bugle often follows notes of the upper harmonic series, but scientists say the sound is probably not generated by overtones. Although the exact mechanisms of how an elk creates these high-pitched sounds are still not completely understood, biologists argue that they likely result from tremendous tension in the elk’s vocal folds, which may produce an extremely high fundamental frequency. Although it is rare, female elk can also make a variation on the bugle call. Click here for more elk sounds.

Sources: NatureServe; Journal of Experimental Biology

The Sonoran Desert stretches from Arizona into Mexico and is home to more than550 vertebrate species, including 350 different birds, 20 amphibians, 60 mammals and about 100 reptiles.

In summer, monsoon rainstorms typically occur from July to mid-September as huge thunderheads move inland from the Gulf of California and the Gulf of Mexico. The rains bring momentary relief from the triple digit-heat, and the animals emerge in full-voiced choruses.

In mid-August of this year, the Western Soundscape Archive visited the desert’s southern Arizona region and made recordings at Saguaro National Park and its surrounding areas (view slideshow). It had rained a day prior to our visit, and the birds were especially active in King Canyon in the Park’s Tucson Mountains district. Further west, rare Sonoran green toads called from a flooded roadside ditch, defying the usually arid landscape. Hear selections.

Sources: Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, Saguaro National Park

Swift Fox Vulpes velox

The Swift Fox is said to be named for its speed and quickness, and has been clocked running up to 37 mph. It is found in the western and central United States and parts of Canada.While still somewhat widespread, this small fox (measuring 31 inches from head to tail) has disappeared from 60% of its former range due to “habitat loss and degradation, interspecific competition,” and other factors, according to the conservation data center NatureServe. It had disappeared completely from the wild in Canada until successful reintroductions began there in 1983.

The Swift Fox can often be found in open prairies or desert plains, and some sagebrush steppe habitat. The species will dig its own burrow for use as a den, or will take over existing burrows of other species such as badgers or prairie dogs.

Sources: NatureServe; Cochrane Ecological Institute

Short-eared Owl Asio flammeus

The Short-eared Owl, Asio flammeus has a reputation for being relatively quiet as owls go. But that perception is being challenged as more audio recordings are made. Calls range from barks and antagonistic screams, to aerial wing claps and rarely recorded hoots.This medium-sized owl is widely distributed across the world, and is generally most active from late afternoon to dawn. Typical habitat in the western United States includes open areas such as grasslands, shrub-steppe and coastal marshes, where the owls commonly feed on rodents and other small mammals, as well as occasional small birds and insects.

According to the conservation database NatureServe, the species appears to be secure due to its wide distribution, but may be declining in some areas due to habitat loss.

Sources: NatureServe

Wyoming Toad Bufo baxteri

The Wyoming Toad, Bufo baxteri is among the rarest amphibians in North America. It is found primarily at the Mortenson Lake National Wildlife Refuge near Laramie, Wyoming, where biologists estimate that 27 breeding adults still remain in the wild. The species is also maintained through numerous captive breeding programs around the country.According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, insecticides, changing agricultural practices, increased predation, disease, and climatic changes may have spurred the decline. The amphibian chytrid fungus, which has devastated frog and toad populations around the world has also recently been reported in captive and wild populations, according to the agency.

The Wyoming Toad typically calls from mid-May to early June.

Sources: US Fish and Wildlife Service; IUCN Global Amphibian Assessment

Photo copyright Larry Master, www.masterimages.org

Burrowing Owl Athene cunicularia

The Burrowing Owl, Athene cunicularia, has a wide variety of vocalizations, ranging from courtship calls and alarm chatter, to defensive rattlesnake mimics (click to hear some of these sounds). These long-legged owls prefer flat, open areas with little or no vegetation, and make their nests in the abandoned burrows of badgers, ground squirrels and other animals.The species breeds in southwestern Canada, the western United States and Mexico, with subspecies also occurring in Florida and parts of the West Indies.

Widespread distribution in North America makes this bird relatively common in some areas, but habitat alteration and other factors are causing population declines. The Burrowing Owl is listed as a Bird of Conservation Concern by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NatureServe).

American Beaver Castor canadensis

The American Beaver, Castor canadensis, is a large rodent that occurs throughout most of North America. The species may be found in permanent slow moving streams, ponds, small lakes, and reservoirs. Beaver are mainly nocturnal but are occasionally seen during the day. They do not hibernate, but may become less active during the winter.The species makes a variety of sounds, from whines, hisses and growls, to loud “tail slaps” that signal an alarm. Chewing and gnawing sounds are also common.

Beaver cut trees to build dams and water diversions, sometimes creating large ponds. Lodges of sticks and mud are often constructed near these ponds and are used by beaver families for shelter, food storage, and the rearing of young.

Females may have one litter of one to nine young each year during the spring or early summer. Beaver are herbivores, eating primarily woody material, such as aspen, in the winter, and green aquatic and riparian vegetation in the summer. The beaver is easily distinguished because of its large size and large paddle-like tail.

Source: Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and the Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America.

Relict Leopord Frog Rana onca

The Relict Leopard Frog, Rana onca, was thought to be extinct until small populations were rediscovered in southern Nevada in the early 1990s. The frog is now found in only a few locations in Nevada and Arizona, and is believed to have disappeared from its former range in Utah. It is classified as “Endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and is a candidate for listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. An estimated 1,000 to 2,500 individuals of the species remain, according to the conservation database NatureServe, which lists such ongoing threats to the frog as “habitat alteration and fragmentation, direct effects of non-native aquatic species, and the currently small population size.” In the spring of 2008, the Western Soundscape Archive visited the Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Arizona and made several hours of field recordings of the Relict Leopard Frog and its surrounding habitat (source: NatureServe).

|

|

|

Relict Leopard Frog egg mass |

Conservation biologist Dana Drake spots a frog during a survey |

Relict Leopard Frog habitat in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area |

Thanks to the Relict Leopard Frog Conservation Program at the Public Lands Institute, University of Nevada at Las Vegas, and the National Park Service for their help with this recording project.

Bottom row photos copyright 2008, Jeff Rice

Columbia Spotted Frog Rana luteiventris

Columbia Spotted Frog Rana luteiventris

The Columbia spotted frog, Rana luteiventris, ranges from southeast Alaska through Alberta, Canada, and into Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and disjunct areas of Nevada and Utah. In Utah, isolated Columbia spotted frog populations exist in the West Desert and along the Wasatch Front. Unfortunately, habitat degradation and loss have led to declines in many of these populations, especially those along the Wasatch Front, precipitating the inclusion of the species on the Utah Sensitive Species List. With a goal of recovering the Columbia spotted frog, several government agencies are working cooperatively under a Conservation Agreement to eliminate or significantly reduce the threats facing the species (source: Utah Division of Wildlife Resources).